Preface

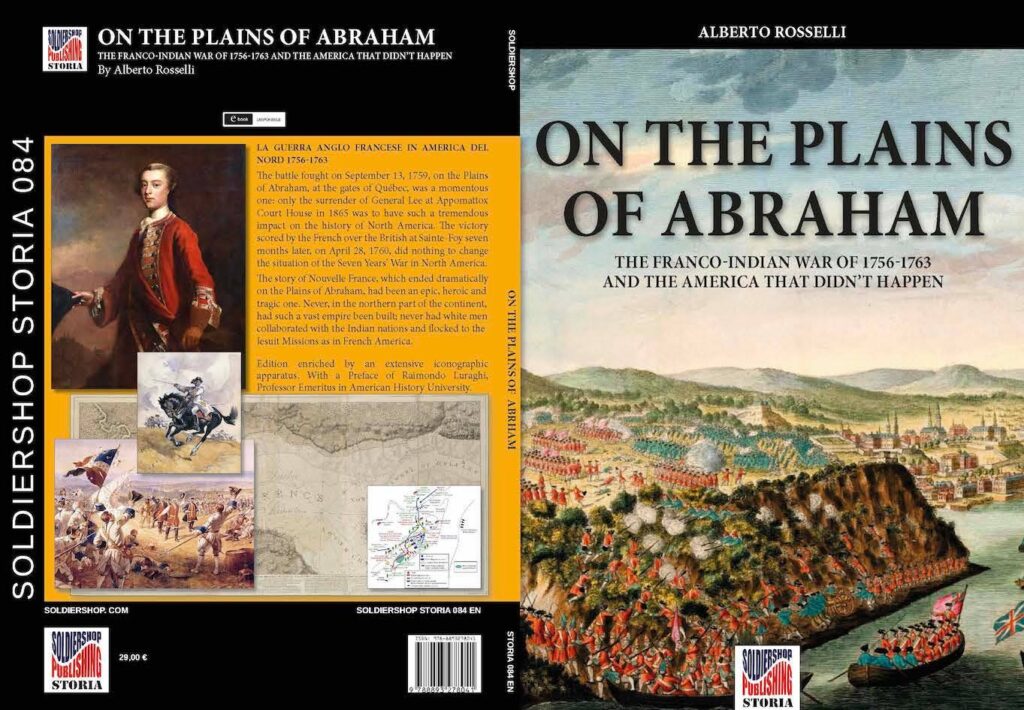

The battle fought on September 13, 1759, on the Plains of Abraham, at the gates of Quebec, was a momentous one: only the surrender of General Lee at Appomattox Court House in 1865 was to have such a tremendous impact on the history of North America. The victory scored by the French over the British at Sainte Foy seven months later, on April 28, 1760, did nothing to change the situation: Ah! A single warship, and the place would have been ours! said a French officer speaking of Quebec, to whom his English captor answered: You are quite right!. Such words underscore the true cause of the French defeat in the war for Canada: the British had command of the sea, and after the fall of Quebec in 1759 and French failure to retake it through lack of seapower, the empire of New France was doomed. Had Montcalm won the battle and overcome Wolfe, everything would have been different; or rather, had he stayed inside the fortress, waiting for Bougainville and his Indian allies to arrive and strike the vulnerable rear of Wolfes army, events would have taken a different turn Still, this is merely empty speculation: events developed as they did, and not as they might have done&

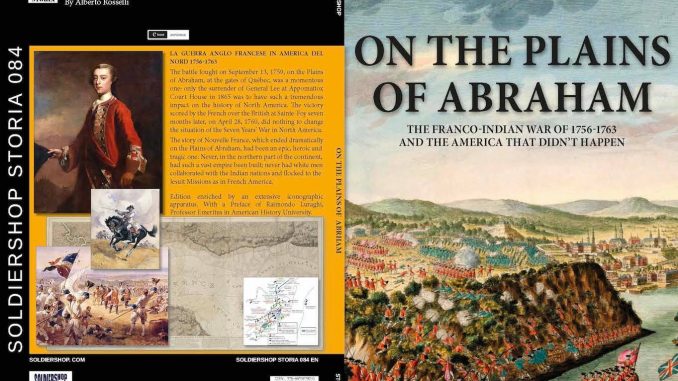

The story of Nouvelle France, which ended dramatically on the Plains of Abraham, had been an epic, heroic and tragic one. Never, in the northern part of the continent, had such a vast empire been built; never had white men collaborated with the Indian nations and flocked to the Jesuit Missions as in French America. First Cartier, then Champlain had made the fateful choice of the rock and peninsula of Quebec as the site of the future capital of New France. Then de Maisonneuve had founded Montreal in the face of the Iroquois menace and the Jesuit missionaries had marched into the wilderness, defying the primeval forest, the rapids of the mighty rivers, the harsh climate and the terrible Iroquois, to organise a veritable chain of missions. This had cost the French colonists, missionaries and explorers sacrifices and much blood: the internecine struggle between Indian tribes had put them on a collision course with the fearsome Iroquois. Settlements had been destroyed and missionaries martyred; yet in the end French tenacity had triumphed. Now, with the defeat at Quebec it was all over. The River of Cartier wrote Bernard DeVoto, was English. Champlain, Frontenac, La Salle, Jolliet, the martyred Jesuits, Perrot, Duluth, Vérendrye, the shining company of great, farseeing men moved beyond the sunset into the dark, leaving North America only a memory of their dream. As Francis Parkman said, The most momentous and far-reaching question ever brought to issue on this Continent was: Shall the United States be one nation or two?. Yet thiswas really only one of two great issues on which the destiny of the continent depended. The heroic story of the French empire in North America deserved an end worthy of an epic poem: and such was the Battle of Quebec. This is why it has always exercised such fascination on readers, historians and scholars alike and not only in the New World. That French writers such as Etienne Salone should be attracted by the epics of Nouvelle Franceis fairly predictable. Yet Alberto Rosselli is an Italian: and I hear the inevitable question arise: why should he be interested in the history of New France?.Rosselli was a very thoughtful and intuitive young student attending the school of North American history at the University of Genoa.When I founded it in the distant academic year 1964-65, this was the first school in Italy dedicated wholly to North American studies, starting from the tenuous beginnings of the colonial era, when Canada was little more than a place on a map and the United States still lay concealed in the distant future. Much time was given over in Genoa to the history of the French American empire; and students of the Genoese school were the first in Italy to discover the fascinating history of New France. Some of those who fell under its spell were fortunate enough to receive Canadian research grants and travel across the Atlantic to study French Canadian history under such scholars as the late William J. Eccles, on whom the University of Genoa conferred an honorary degree. A bright student, Alberto Rosselli started working very early in this field. His choice of the Battle of Quebec as the subject of his early research grew from his graduation thesis, which, in turn, generated this dense and rich book.In my opinion, it is right that an Italian scholar should have dedicated himself to such a subject, for he was and is able to bring to Canadian studies a refreshing perspective, even a new dimension. Uninvolved in the (sometimes nasty) quarrels between francophone and anglophone historians, he has an impartial viewpoint that is not only free from prejudice but also applies a long historical perspective that allows him to look at events from a distance perhaps meaning that he can better distinguish between light and shadow than historians too closely involved in local situations and problems. At any rate, this book is a remarkable contribution to the study of an historical saga that does not cease to fascinate scholars and general readers alike and it offers a key to a fuller understanding of the complex problems of modern-day North-America.

Raimondo Luraghi

Professor Emeritus in American History University of Genoa, Italy.

Lascia un commento

Devi essere connesso per inviare un commento.