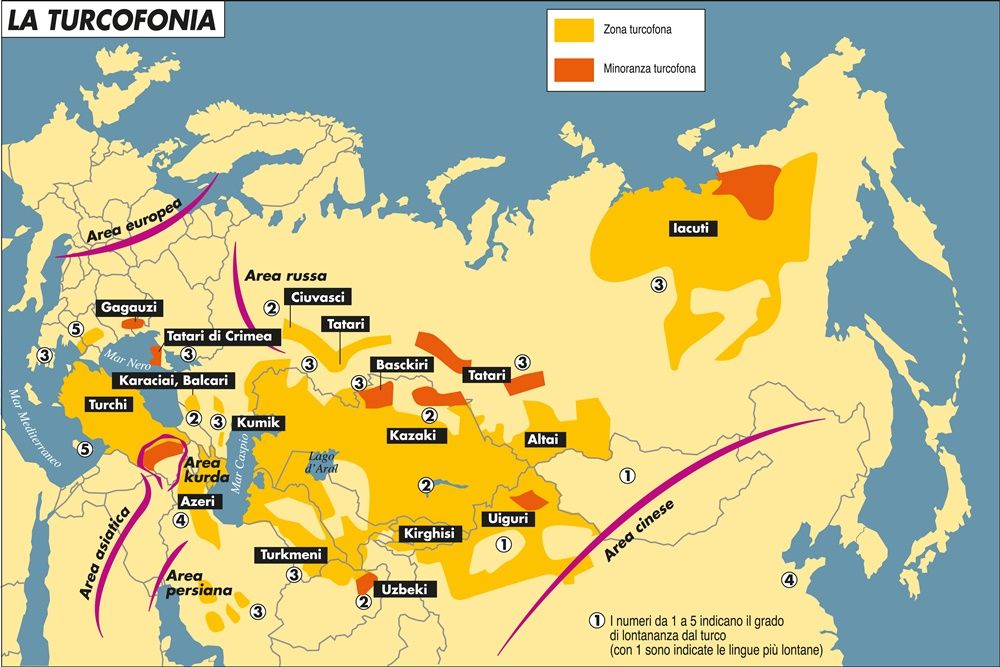

In sintonia con la sua mai sopita propensione imperialista in chiave ‘neo-ottomana’ ‘panturanista’ (il ‘panturanismo’ è una dottrina geopolitica formulata dal linguista ed etnologo ungherese Arminius Vambery alla metà del XIX secolo) la Turchia di Recep Tayyp Erdogan sta cercando di allargare la sua influenza economica, diplomatica e militare ai Paesi turcofoni dell’Asia centrale.

Trattasi di un’operazione decisamente ambiziosa, ma abbastanza rischiosa in quanto un domani potrebbe metterla in rotta collisione con la Russia di Vladimir Putin e con la Cina di Xi Jinping, potenze con le quali, almeno per il momento, la Turchia mantiene discreti se non buoni rapporti. L’attuale processo di avvicinamento di Ankara verso i BRICs (unione delle economie mondiali emergenti, di cui fanno parte Brasile, Russia, India e Cina, Sudafrica, Egitto, Emirati Arabi Uniti, Etiopia ed Iran: un blocco che vale oltre il 40% dell’economia mondiale) confermerebbe questa tendenza, se non ci fossero di mezzo le suddette mire egemoniche del ‘sultano’ turco che, lo scorso 2 settembre 2024, alla vigilia del 16mo meeting delle Potenze emergenti (Astana, Kazakistan, 22-24 ottobre), ha chiesto l’adesione ufficiale al gruppo.

Il Presidente russo Vladimir Putin.

Ora, il premier Erdogan spera di poter rafforzare i legami etnici e linguistici della Turchia con il Centro Asia turcofono (Kazakistan, Kirghizistan, Turkmenistan e Uzbekistan), regione ricca di idrocarburi, gas e minerali rari, per esaltare il proprio ruolo in quest’area fino ad oggi controllata da Russia e Cina. Secondo la politologa turca Chagdash Ungor “uno dei vantaggi più significativi di cui gode la Turchia nei confronti di russi e Cina è il suo soft power. Se da una parte Mosca prevale nelle questioni della sicurezza e dell’esercizio della forza militare, e Pechino per quanto concerne la sfera economica, nessuno dei due può vantare l’innegabile peso che esercitano le relazioni culturali e linguistiche tra Ankara e i popoli dell’Asia centrale”. Ed è proprio in virtù di questo legame che Erdogan preme per allargare ad oriente le sue prospettive egemoniche, cosa non gradita a Pechino (già attiva in Kazakistan e Uzbekistan, ed anche in Afghanistan, con molte sue imprese) e soprattutto a Mosca che desidera mantenere neutrali – ma alleati – i Paesi centroasiatici aderenti alla CSI, cioè i già citati Kazakistan, Kirghizistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan con l’aggiunta del Tagikistan.

L’attivismo del presidente turco va anche interpretato come una mossa per ridurre la sofferta dipendenza di Ankara dalla UE, come spiega la professoressa Tatiana Mitrova, dell’Institut Français des Relations Internationales di Parigi “le politiche turche accentuano di fatto il disagio della Russia, che si scontra con i cambiamenti radicali della sua logistica, visto che la maggior parte degli itinerari verso Occidente risultano ormai bloccati”. Anche gli Stati Uniti, del resto, pongono molta attenzione all’Asia Centrale, cercando di impedire a Mosca di trovare vie d’uscita al suo isolamento e di trattenere la crescente influenza della Cina, e questo potrebbe favorire una convergenza d’interessi tra Washington ed Ankara, anche se quest’ultima si sta dimostrando molto ostile nei confronti di Israele e accomodante con una Russia intenzionata a fare piazza pulita dell’Ucraina appoggiata dalla UE e da Gran Bretagna e Stati Uniti. D’altra parte, continua la Mitrova “la Turchia rimane un importante alleato per la Nato, soprattutto nel confronto con Cina e Russia”, quest’ultima abituata fin dai tempi del Grande Gioco ottocentesco a considerare i Paesi del cosiddetto cortile asiatico come un’area naturale della propria sfera d’influenza. Ragion per cui – lo ripetiamo – Mosca non può certo rallegrarsi dell’attivismo di Erdogan nella regione, non impedendo, tuttavia, a Putin di mantenere, obtorto collo, buoni rapporti con Erdogan per l’aggiramento delle sanzioni imposte dalla UE al Cremlino. Tutto ciò almeno allo stato attuale.

Il Presidente turco Recep Tayyp Erdogan.

In prospettiva futura, e in concomitanza con l’invadenza turca in Asia Centrale, non è infatti improbabile che Mosca intenda rivendicare il proprio primato, innescando una fase di concorrenza aggressiva nei confronti della potenza anatolica. In un modo o nell’altro, secondo i pronostici degli esperti, l’Asia Centrale potrebbe diventare una polveriera la cui miccia è in mano al ‘sultano’ Erdogan, intenzionato a rivestire un ruolo di guida non soltanto economica ma anche culturale e militare nella partita che si sta profilando non soltanto in Asia Centrale, ma anche nel Caucaso, con il suo deciso appoggio al governo del ricco Azerbaigian petrolifero, impegnato a sua volta nella sanguinosa contesa del Nagorno Karabak con l’Armenia cristiana, un tempo protetta dalla Russia ed ora abbandonata a se stessa. Il tutto sullo sfondo del duplice conflitto russo-ucraino e israelo-palestinese-iraniano che vedono in gioco, sullo sfondo, il ruolo di una potenza mondiale piuttosto logora, cioè gli Stati Uniti, che a partire dallo sgombero dell’Afghanistan dell’agosto del 2021, non sembra più in grado di fare valere la propria forza nell’Asia di mezzo.

The Panturanist ideology behind Recep Erdoğan’s expansionist plans in Central Asia, and the possible collision with Putin’s Russia.

by Alberto Rosselli

In tune with its never dormant imperialist inclination in a ‘neo-Ottoman’ ‘panturanist’ key (‘panturanism’ is a geopolitical doctrine formulated by the Hungarian linguist and ethnologist Arminius Vambery in the mid-19th century) Recep Tayyp Erdogan’s Turkey is trying to extend its economic, diplomatic and military influence to the Turkophone countries of Central Asia.

This is a decidedly ambitious operation, but quite risky in that it could one day put it on a collision course with Vladimir Putin’s Russia and Xi Jinping’s China, powers with which, at least for the moment, Turkey maintains discrete if not good relations. Ankara’s current process of rapprochement towards the BRICs (union of the world’s emerging economies, which include Brazil, Russia, India and China, South Africa, Egypt, United Arab Emirates, Ethiopia and Iran: a bloc worth over 40% of the world economy) would confirm this trend, were it not for the aforementioned hegemonic aims of the Turkish ‘sultan’ who, on 2 September 2024, on the eve of the 16th meeting of the Emerging Powers (Astana, Kazakhstan, 22-24 October), requested official membership of the group.

Now, Prime Minister Erdogan hopes to strengthen Turkey’s ethnic and linguistic ties with Turkish-speaking Central Asia (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan), a region rich in hydrocarbons, gas and rare minerals, in order to enhance its role in this area hitherto controlled by Russia and China. According to Turkish political scientist Chagdash Ungor, ‘one of the most significant advantages Turkey enjoys over the Russians and China is its soft power. While Moscow prevails in matters of security and the exercise of military force, and Beijing in the economic sphere, neither can boast the undeniable weight exerted by the cultural and linguistic relations between Ankara and the peoples of Central Asia‘. And it is precisely in virtue of this bond that Erdogan is pressing to expand his hegemonic perspectives to the East, something that is not appreciated by Beijing (already active in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, and also in Afghanistan, with many of its enterprises) and above all by Moscow, which wishes to keep the Central Asian countries that are CIS members neutral – but allies – that is, the aforementioned Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, with the addition of Tajikistan.

The Turkish president’s activism is also to be interpreted as a move to reduce Ankara’s painful dependence on the EU, as Professor Tatiana Mitrova of the Institut Français des Relations Internationales in Paris explains: ‘Turkish policies actually accentuate Russia’s unease, which is clashing with the radical changes in its logistics, given that most routes to the West are now blocked’. The United States, moreover, is also paying a great deal of attention to Central Asia, trying to prevent Moscow from finding ways out of its isolation and to hold back China’s growing influence, and this could favour a convergence of interests between Washington and Ankara, even if the latter is proving to be very hostile towards Israel and accommodating with a Russia intent on wiping out Ukraine supported by the EU and Great Britain and the United States. On the other hand, Mitrova continues, ‘Turkey remains an important ally for NATO, especially in the confrontation with China and Russia,’ the latter having been accustomed since the days of the 19th century Great Game to considering the countries of the so-called Asian backyard as a natural part of its sphere of influence. Reason why – we repeat – Moscow certainly cannot rejoice at Erdogan’s activism in the region, not preventing, however, Putin from maintaining, obtorto collo, good relations with Erdogan for the circumvention of the sanctions imposed by the EU on the Kremlin. All this, at least at present.

In the future, and in conjunction with the Turkish encroachment in Central Asia, it is in fact not unlikely that Moscow intends to claim its primacy, triggering a phase of aggressive competition against the Anatolian power. One way or another, according to experts’ predictions, Central Asia could become a powder keg whose fuse is in the hands of the “sultan” Erdogan, who is intent on playing a leading role not only economically but also culturally and militarily in the looming game not only in Central Asia, but also in the Caucasus, with his decisive support for the government of oil-rich Azerbaijan, itself engaged in the bloody Nagorno Karabak dispute with Christian Armenia, once protected by Russia and now abandoned to itself. All this against the backdrop of the dual Russian-Ukrainian and Israeli-Palestinian-Iranian conflicts, which see at stake the role of a rather frayed world power, namely the United States, which, since the clearing of Afghanistan in August 2021, no longer seems able to assert its strength in Middle Asia.

Lascia un commento

Devi essere connesso per inviare un commento.