Soldati e carri giapponesi in Cina.

Japanese who fought against the chinese communists 1945-1949.

Following the Pacific War, Japan lost all the colonies or occupied areas and all military units in Japan and elsewhere were officially disarmed. Under these circumstances, the Japanese government did not have the ability to formulate a new China policy. But some Japanese stayed in China and collaborated with the Nationalist Army. I will examine those activities mainly in Shanxi province and point out some aspects which were different from the logic of the Cold War. In the last stage of the war, the First Army, under the command and control of the China Expeditionary Army, stayed at Taiyuan, a major city in Shanxi. In May 1945, in the face of Nazi Germany’s defeat, a group of the First Army’s staff developed the idea of preserving the force for Japanese reconstruction. This idea, according to Hiroshi Jono, a political adviser to the government of Shanxi province, meant that some Japanese forces should remain outside Japan, maintain their organizations, and preserve their power for the purpose of reconstructing Japan. Besides Jono, the leading members advocating this idea included General Yamaoka and Major Iwata. General Raishiro Sumita, commander of First Army, seemed tacitly to approve this idea. The staff group, Jono recalled, predicted that Japan’s defeat was inevitable and that Japan would be occupied and disarmed by the Allied Powers after the surrender. However, the staff group thought, if Japanese independence were restored, the new Army would be necessary for new Japan.

Hiroshi Jono (la foto risale alla data del suo arresto da parte delle forze comuniste cinesi).

Truppe comuniste cinesi (1949).

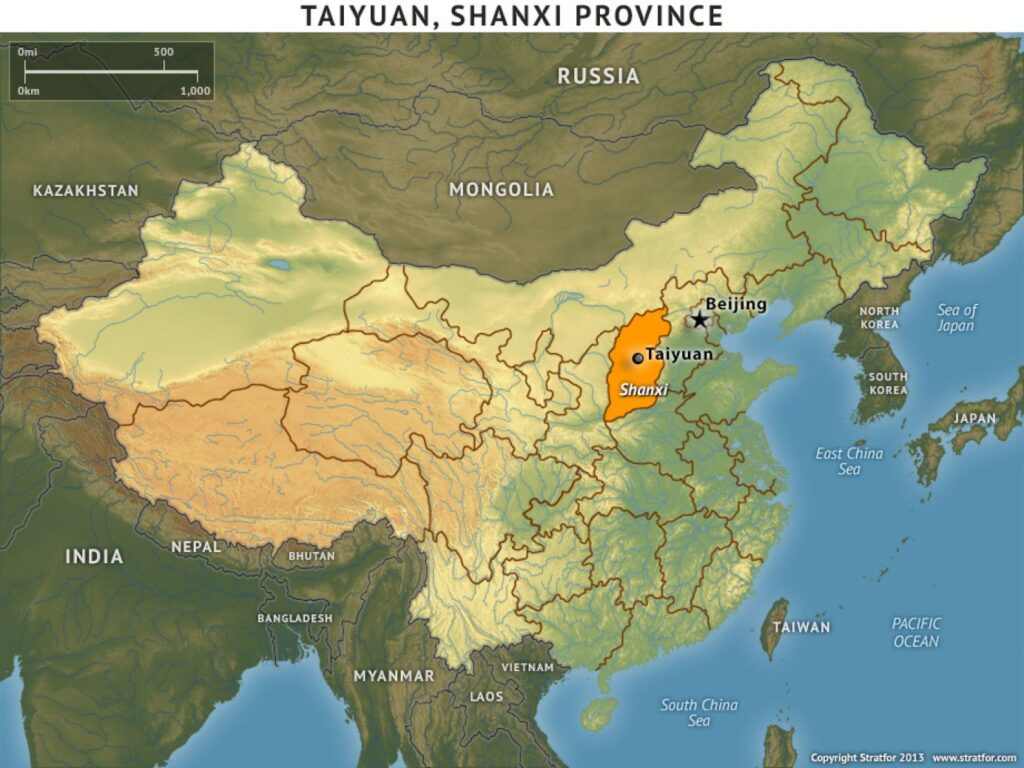

Therefore, some troops deployed in foreign countries and their equipment should be retained for that purpose. Those who advocated this idea considered Shanxi the most suitable place to implement their plan. In addition, those staff officers were concerned about the economic implications of the forces preserved for reconstruction, thinking that a prosperous market and access to natural resources would be indispensable for recovery. The First Army force should thus secure a suitable area: Shanxi.

Il generale Raishiro Sumita.

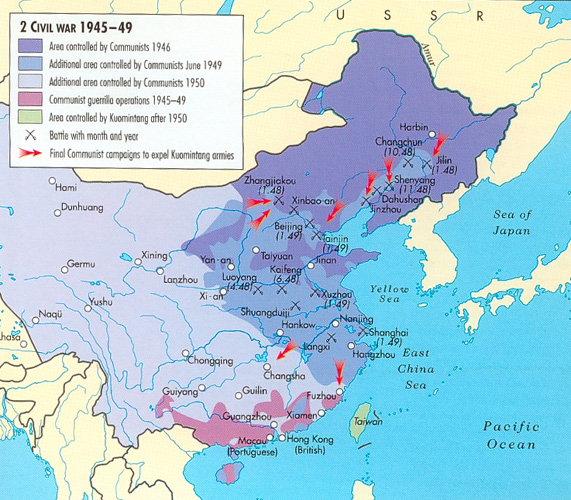

Hiroshi Jono pointed out in his memoir some reasons why Shanxi was the best area. While Shanxi province was theoretically under the Nationalist government, it was actually ruled almost independently of Chiang Kai-shek by Governor Yan Xishan, who was pro-Japanese. The Japanese staff officers, therefore, expected that Yan would allow the Japanese Army to stay in Shanxi because he needed its help for his battle against the Communists. Yan Xishan actually tried to utilize the Japanese forces, weapons, and materials. Just after the war’s end, Yan asked General Sumita to transfer Japanese equipment to him and that Japanese troops remain in Shanxi under his command. Sumita initially refused, saying that it was senseless for the Army to engage in hostilities without the Japanese government’s order. Yan pressed Sumita strongly, however, and the general finally agreed, provided that Japanese soldiers were first discharged from military service and then volunteered to serve under Yan. About two thousand Japanese soldiers took part in this program when it was established in the spring of 1946; the last unit fought against the Communists in Shanxi until April 1949.

Mitraglieri cinesi nazionalisti.

By the spring of 1949, the number of Japanese soldiers had decreased to one hundred, and many of them lost their lives in the final battle. Although the original idea had been that the Japanese volunteer force in Shanxi would assist Japan’s reconstruction, it was destined to be a deserted force. Neither the Japanese government nor the senior officials of the former Japanese First Army would accept the volunteer activities in Shanxi, because it was a violation of the Potsdam Declaration. One junior officer who refused to participate in the new army recalled that the staff recruited soldiers systematically, giving enlisted men an exaggerated picture of the misery that awaited them if they returned to Japan. They even created a false pamphlet saying that if the soldiers returned to Japan, they would be sent to a prison in New Guinea as war criminals. he Japanese government knew of the activity in Shanxi and opposed the volunteer army plan. The First Ministry of Repatriation (formerly the Army Ministry) several times ordered the activities in Shanxi halted and sent an officer, Shun’ichi Miyazaki, to investigate the situation. Miyazaki reported in April 1946, that Yan Xishan was aiming at establishing his own independent kingdom with the help of his Japanese volunteer army. Miyazaki opposed this use of Japanese forces and recommended that the staff officers who insisted on remaining in Shanxi should be transferred elsewhere and that repatriation of Japanese soldiers in Shanxi begin as soon as possible, with the cooperation of U.S. troops. Even Yasuji Okamura, the former commander of the China Expeditionary Army, who advocated cooperation with the GMD army after the Nationalist government moved to Taiwan, objected to the Shanxi project. United States leaders were also aware, to some extent, of the events in Shanxi province, and regarded it as injurious to the American program in China and to the Marshall Mission. Governor Yan was an obstacle to U.S. policy in China, in part because he did not obey the cease-fire that Marshall had helped to negotiate and continued to battle against the Communists, and in part because he was violating the Allied Powers’ order for disarming Japanese troops. When General Marshall visited Taiyuan 3–4 March 1946, he and the other members of the Committee of Three met some generals in Yan’s army and demanded the disarmament of the Japanese troops. Yan needed the Japanese forces, however, so he and his Japanese officers ignored Marshall’s request. The Japanese troops were camouflaged by officially disbanding them and hiding them in mountainous areas and retaining their organization. The Nationalist government not only did not support Yan Xishan, it strongly opposed his use of Japanese troops. When Shun’ichi Miyazaki, the Japanese officer investigating the Shanxi issue, met Yan, he found that Yan had refused to implement the directives from Chinese Army Headquarters ordering the disarmament of his Japanese troops. Colonel Ulmont W. Holly, American member of Field Team 3, reported that Yan “repeats the orders received from[Marshall Mission] Executive Headquarters to his Field Commanders, but does not issue directives of his own to see that they are carried out.”This was not the first time that Yan had ignored orders from the national government or Executive Headquarters. The national government had a long history of trouble in dealing with him. Yan, while anti-Communist, was an old-style warlord and not a man who understood the local situation in terms of U.S.-Soviet international rivalry; he merely wished to secure Shanxi. Yan’s ambitions might fit the old-fashioned Japanese view of “weak and divided China,” but the Imperial Japan that had invaded China with this view no longer existed, and the postwar Japanese government could not recognize his Japanese troop project, making it an abandoned army. Possibly the Japanese officers who advocated this project could have exploited the U.S.-Soviet conflict, but they had no long-range vision of the Cold War and their plan was thus destined to failure. Moreover, the whole concept of the force preserved for Japanese reconstruction was vague and unjustifiable, ignoring as it did Japanese responsibility for the Asian war. As it became clear to Yan’s Japanese mercenaries that their idea of assisting Japan’s reconstruction was irrelevant, the officers sought to redefine their role. Hiroshi Jono, the troops’ political adviser, sought to revive the empty argument of an Asian anti-Western coalition. In his memoir, Jono wrote that the Japanese in Shanxi should help to strengthen Yan’s regime first, then let Yan persuade the Nationalists to cooperate with Japan, and subsequently Japan and China could form an anti-Western third-force coalition to exploit the Soviet-American conflict. A reflection of obsolete anti-Western sentiments, his plan was doomed to failure. Philosophically the Japanese effort in Shanxi was a backward-looking amalgam of obsolete views.

Fonte: (http://www.marshallfoundation.org/pdf/2 … 0views.pdf

Soldati nazionalisti cinesi.

Mappa Guerra Civile Cinese.

Mappa Cina (Provincia di Shanxi).

)

Lascia un commento

Devi essere connesso per inviare un commento.