In 1759 the French Naval force, severely crippled by numerous defeats at the hands of the British fleet during the Seven Years’ War, entered a period of profound organisational and structural crisis from which it would emerge only many years after the end of the war between London and Versailles.

Between 20th and 21st November 1759, the British fleet definitively defeated their flagging enemy in the cold waters off the coast of Quiberon in Brittany. Admiral Hawke’s 30 ships conquered most of Admiral Conflans’ 21 vessels, thus breaking up the last French fleet able to oppose the British navy. The defeat at Quiberon (historically known as the “Battle of Conflans” or “of the Cardinals”) forced the French to abandon any further strategic attacks. The French king was therefore obliged to give up minister Choiseul’s cherished and ambitious plans to invade the enemy island, and also to abandon the colonies still in his possession. The British Admiralty, now absolute ruler of the Ocean, was tightening a noose around the neck of their historical enemy that it had been carefully preparing since the beginning of the century.

Since the beginning of the 18th century the French colonisation process of North America, Indian West Africa and the Caribbean (which had so swiftly developed in the 17th century) began to meet with opposition from the British colonising strategy in operation at the same time. The French seafaring and land force, like Spain’s, was now in a strong decline and had to face an increasing number of British merchant and military fleets on the Ocean. The complex network of commercial, political and strategic interests forming the basis of the contrasting colonial development of the two European nations had already laid the foundations during the first decade of the 18th century for friction which would soon become a full-blown conflict. Having defeated Spain during the brief war of 1739, England had been involved, along with France, in the War of Austrian Succession; this conflict highlighted for the first time the discrepancy between the naval forces of the two Powers; indeed, during this war English proved to possess far superior naval resources to those of the French. Although France was obliged to face England both across the Ocean and nearer to home, the government neglected the efficiency of its merchant and military navy, mistakenly believing that the outcome of any war would ultimately be decided on landbound battlefields on the Old Continent. As time passed, and despite the initial and obvious proof to the contrary, (England’s fleet had managed to snatch away the North American Dutch colonies) Versailles did not deem it necessary to look for remedies by strengthening its naval resources. During the subsequent Seven Years’ War against England for supremacy over the Old and New Worlds, France again failed to act, following a military strategy which favoured land operations to the detriment of seafaring ones. This clear lack of tactical foresight soon lost France her richest colonies, most of them to England, who had now become the only legitimate world power.

Before the outbreak of the Seven Years’ War, the thirteen English colonies in North America were able to supply and sustain the forces protecting the transatlantic trade routes and colonies thanks to their port and dockyard structures and infrastructures (freight terminals like Halifax and New York already boasted equipment comparable to that of English ports). Contrarily New France (Canada) and French Louisiana had hardly any important landing places (Louisburg, Quebec and Nouvelle Orléans were simply equipped fortresses) and therefore were not able to fulfil the same role due to a lack of specialised personnel and equipment.

In order to better understand the significance of the Anglo-French conflict halfway through the 18th century we should first briefly summarise the respective situations of the two naval forces in earlier decades.

One of the best known modern naval historians, Campbell, states that in 1727, the British navy possessed 84 warships with 60 cannons each; 40 with 50 cannons and 54 frigates and smaller vessels. In 1734 though, it was reduced to 70 warships and 19 with 50 cannons. However in 1744 after four years of conflict with Spain, the fleet numbered 90 warships and 84 frigates.

Campbell estimates that in the same period the French navy possessed 45 warships and 67 frigates. In 1747, towards the end of the first bout of conflict with England, the Spanish Royal Navy seems to have been reduced to barely 22 warships and the French navy to 31, while the British increased to reach a total of 126 vessels. Experts in matters regarding the French navy unanimously underline the poor conditions of the French navy and the worse state of the national arsenals and dockyards, which lacked structures and even materials. This negligent state of affairs continued more or less for the length of the of the war in the 18th century or at least until 1760 when, rather late in the day, Versailles realised the importance of the naval element.

Having said this, we must not be seduced into the common belief that the French naval industry was inferior to the British, not only in terms of productivity but also in construction techniques. This is not the case, at least for projects and constructions carried out by the French between 1740 and 1800. During that period the ships laid down and launched by the French were of a high constructional standard and had greater displacement than those built by the English, despite being considerably fewer in number.

From the first half of the 18th century onwards France did little to counter the British policy of reinforcement of its merchant and military navy, although the survival of French colonies in North America India and West Africa depended on the quality and quantity of maritime links. When the Seven Years’ War began France did not consider it necessary to arm its navy sufficiently, and gave priority to equipping its armies. England, on the other hand, did not engage in land battle, on European soil, entrusting to Prussia the task of facing the fearsome French armies and their allies; instead, England concentrated on constructing those fleets which would allow the nation to freeze France economically. It can undoubtedly be stated that the English won the Seven Years’ War on the sea, thus obtaining extensive territory, riches and indisputable international prestige.

In July 1755, before England and France were at war, London ordered its fleet to patrol the French coast between Capo Ognissanti and Capo Finisterre with the aim of capturing or sinking the greatest possible number of enemy ships. England inflicted severe financial damage on France through these “pirating” manoeuvres, capturing in 1755 300 French merchant ships and 6000 officers and crew.

In the face of such blatant hostility Versailles protested by simply breaking off diplomatic relations with London and calling home its ambassador. This attitude, however, marked by excessive caution – indeed, a kind of acquiescence – disguised other intentions. France recognised its naval inferiority and with this low profile policy was playing for time in order to secretly re-arm a large naval unit to invade England. A large number of sailing ships, soldiers, arms and supplies were stored in the arsenals of Brest and the Channel. The English were particularly sensitive to the danger of an invasion of their island, after the famous attempt of the Invincible Spanish Armada nearly two centuries previously. Despite the success of its piracy manoeuvres, in 1755 the English government seemed to be in trouble, as almost all its naval units were scattered over the various Oceans, protecting the trade routes. England was therefore obliged to give up – although temporarily – total control of the Mediterranean. On 10th April 1756 12 French battleships set sail from Toulon, under the command of Admiral La Galissonière. The unit had orders to escort a convoy of 150 transport ships (with 15,000 soldiers on board commanded by the Duke of Richelieu) for invasion of the island of Minorca which was occupied by the English. The modest British garrison of Port Mahon (consisting of barely 3000 soldiers) seemed destined to fall. Faced with this situation the Admiralty quickly put together 13 vessels under the orders of Admiral Byng which set sail from Plymouth and reached the waters of Minorca after about six weeks. La Galissonière, who had already reached his destination, attacked the English fleet which, thanks to Byng’s hesitation, was forced to withdraw, leaving Minorca to its fate. A few days later, in fact, the garrison surrendered to the French. The victory was greeted in Versailles with indifference, and worse: “the French naval ministry found it opportune to sell or hire the available ships and equipment on board, in order to earn money for use elsewhere”, narrates Lapeyrouse Bonfils in his Histoire de la Marine.

Apart from isolated episodes, the French fleet during the Seven Years’ War was always exposed to unnecessary risk and ill-equipped, as Versailles insisted on keeping in the Channel ports his best resources, for the hypothetical attempt to invade England, which never took place. In any case the French naval strategy was always characterised by a distinctly defensive attitude, strongly influenced by the views of Admiral Gravel.

“If two maritime powers are at war,” argued Grivel, “the one with less ships must always avoid battles of uncertain outcome (…). The attitude to be assumed depends above all on the power pf the enemy (…). We will never tire of repeating that whether France fights an inferior or a superior power, she has the possibility of employing two different strategies, radically opposed in their means and ends: a great war, or a war of piracy”.

But Grivel’s opinions were not universally shared in France. Some young officers wondered whether it was possible to guarantee France a real maritime attacking and defence force. Grivel’s theories prevailed, however, passionately defended by theorists like Ramatuelle who actually discouraged conflict with the English naval forces which were held to be stronger and more numerous. “Even if we manage to cause damage to the enemy, what advantage would that give us? A few ships certainly do not represent a great loss to England, as they have so many”. Was it was therefore advisable never to fight England on the seas, as the disconcerting Julien de la Gravière stated in his Guerres Maritimes?

During the Seven Years’ War, France usually chose never to fight its fearsome enemy on the sea, thus demonstrating complete ignorance of the very nature of the war and the places in which it was being fought. In order to defend or extend its colonial possessions in North America, the Caribbean or India, France should in fact have opposed the enemy by attacking and scattering enemy military convoys. The French Admiralty’s pathetic attempts to concentrate all their efforts on equipping a “special” fleet (only a tiny part of which was completed) to transport an invading army to England, were futile. France could hardly have undertaken such a complex manoeuvre against a nation which boasted the strongest war navy in the world. This fleet would certainly not have failed to act against the manoeuvre of an invading army, 80% of which consisted of slow and almost totally disarmed transport vessels. From 1756 to 1763, the French units rarely took to the seas with offensive intentions and on the few occasions when they did, they suffered serious defeats. By leaving the control of the Oceans to the English, France lost all its overseas colonies which could have supplied the nation with precious goods and raw materials. England, on the other hand, was well-protected by her fleet and not only won the first world war in history, but was transformed from a simple island kingdom to a real Empire of global dimensions.

Some experts maintain that during that phase of history France could never have fought England successfully on the Ocean, even in response to a burdensome duty. They support this view saying that the discrepancy between the dockyard production, and the technical expertise of the officers and crew of the two nations was too wide. These experts, mostly French, also maintain that Versailles would not have been able to damage the English forces even with the systematic and coordinated support of a second fleet, like its ally Spain, and this effectively is what happened.

In 1756 the French navy had 63 warships, 45 of which were in good condition although the artillery and equipment on board was inferior in quality and quantity to that possessed by the English. A naval power like Spain, clearly in decline but still a considerable force, numbered 46 warships at the beginning of the Seven Years’ War, all of which were inadequately armed compared to English and French ships. Great Britain, on the other hand, could count on 130 warships (in 1756) without taking into consideration that in 1760 another 120 were being fitted out in its dockyards.

According to Alfred T. Mahan, author of The Influence of Maritime Power on History, during the Seven Years’ War France took for granted England’s naval superiority and was defeated from the very beginning “even though at the beginning France managed to obtain encouraging results. The conquest of Minorca was followed in November of the same year by that of Corsica (the Genoese Republic conceded to France all the fortified ports on the island). France now managed to gain many points over her rival having available bases in Corsica, Provence (Toulon) and the Balearic Islands (Port Mahon)”, at least as far as the Mediterranean war was concerned.

During 1756/7, in Canada, the operations carried out by the French were nearly always successful and the English were unable to effectively support their land armies. A favourable and quite unexpected political opportunity arose (Holland decided not to renew its alliance with England but to retain a neutral position in the conflict) which gave the French the fleeting illusion of having solved a good deal of the thorny problem of the seafaring war. London immediately reacted by declaring a block of all French ports and the halting of all ships, not only French, directed towards those ports: foreign ships considered to all effects “enemies” and subject to capture as legitimate prisoners of war. The English certainly had no scruples since their own security was at stake and they were not excessively worried about the regulations which at that time governed (albeit fairly roughly) navigation and the activities of neutral vessels.

As Mahan explains: “an obvious violation of the rights of neutral nations, like that committed by the English, could only be made by a country confident that it had nothing to fear from others. France however could have used the aggressive attitude of the English Lion, nourished by its sense of power, to its own advantage, to drag Spain and other countries into a war against England.”

Instead of acting in this way France decided to form an alliance with Austria and begin a continental war against Frederick II’s small but fearsome Prussia. The German monarch, surrounded, reacted quickly and energetically and for the first time, formed an alliance with England. Subsequently, in 1756, he invaded Saxony and routed the French and Austrian enemy.

England quickly identified and evaluated the potential advantages of this situation. By allowing the strong and generous Prussia to shoulder the burden of the continental conflict on land, England could dedicate herself to the fulfilment of her true territorial aspirations, which did not lie in Europe but in other locations: North America, India and the Caribbean. So London turned its full attention to the Ocean and overseas colonies, sustaining Frederick the Great with considerable funds obtained from intercontinental trade and shipping only a restricted number of troops to Germany. Thus England forcibly broke France down on all sides, stabbing and attacking her weakest points. This shrewd strategy was the fruit of the enlightened, almost diabolical mind of Prime Minister William Pitt, to whom Britain owes a debt of gratitude: it was thanks to the Prime Minister’s intuition that England became a great world power.

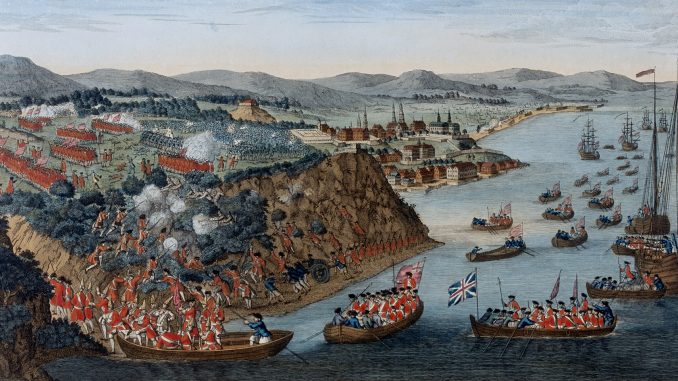

Initially the activity of the English fleet in the North America campaign was less than brilliant. For example, in 1757, the Admiralty decided not to attack the stronghold of Louisburg (defended by 16 French units, some of which were only of small tonnage). The Halifax Command did not want to use the 15 warships available for this operation because at that time they were considered of inferior quality to the French ones. London disapproved of this unwillingness to attack. The echoes of the scandalous Minorca operation (in which the English had lost the island due to the indecisive conduct of Admiral Byng) had not yet died down and Prime Minister Pitt had no intention of gambling the reputation of the Admiralty and his own government. In any case, another year went by before the English decided to make a move against the tactical stronghold of Louisburg. In 1758 the French fort, protected by barely 5 French vessels[1], was attacked by Admiral Boscawen (a decisive officer to whom Pitt had entrusted the delicate mission) with a large squad and 12,000 soldiers. Once Louisburg was taken, the English fleet enjoyed free access to the St. Lawrence estuary, and the following year went upriver again to conquer the capital of New France, Quebec. This time the difficult task of leading the ships up the dangerous river was entrusted to Admiral Saunders, assisted by Admiral Holmes. Meeting with no resistance from the French fleet, the English brought this mission to a brilliant conclusion and reached the bastions of the city. When the commander of the French-Canadian forces in Quebec, General Montcalm, became aware of the situation, he applied in vain to Versailles for the intervention of the French fleet in order to block the English in the river. If a French squad had acted in time, Saunders’ fleet would have been trapped. But the Supreme Command did not consider it opportune to send many units to Quebec’s aid, explaining that any ship would certainly be intercepted by the English fleet at the St. Lawrence estuary before it could reach its destination. It is easy to infer that Versailles continued to see Britain as an invincible monster.

Just as the integrity of the routes linking France to her colonies depended entirely on the fleet, the use of vessels (such as canoes, rafts, schooners and tartanes) would be decisive for the success of a land campaign in North America, a land rich in rivers, watercourses and huge lakes. The English did not hesitate to support their armies with naval corps whose task was to build and equip the indispensable vessels for transportation of men, arms and provisions across the Great Lakes or the wide rivers leading to Canadian territory.[2]

After the fall of Quebec in September 1759, the remaining French-Canadian forces under the command of Vaudreuil retreated to Montreal, the last French outpost of North America, from where an attack was launched the following year against the former capital Quebec, now defended by a moderately numerous English garrison led by General Monckton. Having defeated the English at Saint Foy and forced the enemy to take refuge behind the bastions of the city, Vaudreuil realised that he could not conquer Quebec without the assistance of the Navy. On the other hand, a few days after the French victory at Saint Foy, an English naval squadron came to the aid of the British garrison. “This event,” Mahan recounts, “showed the French the importance of a powerful fleet”. If a French squadron had managed to sail up the St. Lawrence before the enemy, Quebec would surely have fallen into Vaudreuil’s hands. But as we know, things turned out differently. The French governor not only had to give up his plans to reconquer the city but was forced to retreat to Montreal where he surrendered to the British on 8th September 1760.

In the light of the above events, the obvious organisation, structural and numerical inferiority of its naval forces and the lack of adequate political maritime strategy, seem to have been the main factors that lost France the Seven Years’ War. After the first two years of conflict, characterised by humiliating defeats at sea, the French Admiralty decided to concentrate its efforts on a sole and certainly over-ambitious objective – the invasion of England – removing valuable ships and crew intended for other, more important and urgent purposes. The preparations of the landing fleet lasted for years and ultimately were abandoned due to lack of funds, equipment and damage to the arsenals. To counter this threat of invasion, the English fitted out several skilful naval squadrons with the task of defending the channel ports and attacking the enemy dockyards and wood depots. This was all part of the British Admiralty’s tactical plan to defeat France. As well as the aforementioned operations in North America, the Caribbean and India, London arranged the “blocking” of the main enemy freight terminals (like Brest): these suffered numerous effective incursions often followed by small-scale invasions and sabotage. Attacks of this nature forced France to relocate many garrisons along its coast, removing troops and equipment from other fronts. But the British Admiralty went even further. Throughout the conflict, Britain held a squadron in Gibraltar whose precise task was to prevent the French Toulon fleet from venturing beyond the Pillars of Hercules into the Ocean. The activities of the British “Mediterranean” squadron were however secondary to others. Given the almost total absence of enemy forces, the Admiralty was able to organise various expeditions to the most important French colonies of the West Indies (Guadeloupe) and along the West African coast (Senegal). France was thus deprived of the valuable raw materials and products it so badly needed to fund its war economy. Spain’s tardy and imprudent decision to enter the war as France’s ally in 1762 provided the English with new laurels: the insubstantial nature of the Spanish fleet allowed England to easily and profitably pillage Madrid’s rich colonies in the Americas and Philippines.

Meanwhile, the situation surrounding the French bases of the Atlantic coast was deteriorating. Brest was repeatedly attacked or “blocked”. The geographical location of the Breton port conditioned the behaviour both of defenders and potential attackers: it was often difficult for French ships to put out to sea in stormy west wind conditions, while the currents could be dangerous for the English squadrons which often crossed these waters. In order to avoid disaster during bad weather, the English habitually kept their ships safely in Torbay or Plymouth until the favourable summer east winds returned. Thus the effectiveness of France’s largest Atlantic terminal was impaired during the course of the year. Nevertheless, during the war many French convoys commanded by skilful and courageous captains braved the swells to evade the surveillance of English ships.

In 1758 Versailles decided to accelerate preparations for the equipment of the fleet intended for invasion of England. Provisions from the colonies were scarce and the country, deeply involved in war with Frederick II of Prussia on the continent, was beginning to show signs of giving in. Worried by this grave state of affairs, Louis XV decided to entrust the supreme command of military forces to Choiseul. At the beginning of 1759 Choiseul again reduced the time for equipping the invasion squad, without bothering to reinforce the overseas colonies. Most of the arsenals and their personnel were involved in the construction of special flat-bottomed invasion vessels, suitable for transporting troops, four-footed animals, artillery and provisions. According to his plans, an army of 50,000 men would be shipped across the Channel and a second army of 12,000 would land in Scotland. Most of the ships and vessels required for this undertaking were built in the dockyards of Le Havre, Dunkirk, Brest and Rochefort. Choiseul also had two squadrons equipped in Toulon and Brest, which once united would escort the transport ships. But due to the presence of the British Mediterranean squadron anchored in Gibraltar, the two fleets could not meet up and remained separate for the rest of the war. Only then did Versailles decided to shelve this project. Once again, possession of the Rock of Gibraltar allowed Britain to eliminate a serious threat with minimum effort. Ironically in 1757, perhaps England’s most difficult year, Pitt had been overcome by uncharacteristic anxiety and offered to return the Rock to Spain in exchange for that nation’s immediate help in reconquering Minorca.

In August 1759, the French naval squadron from Toulon did however make an attempt to reach the Atlantic and therefore Brest. After repelling an attack led by Admiral Boscawen’s squadron on the route to Toulon, on 5th August, Commodore De La Clue left those waters with 12 ships and pursued the enemy who was retreating to Gibraltar. De La Clue passed through the Straits during the night and entered the Atlantic, where 5 of his ships went off course and ended up in Cadiz. The next day, the commodore faced Boscawen’s entire squadron with the 7 remaining ships, but damage was restricted by the heroism of one of the French captains, a certain De Sabran, who sailed his ship into the fray to allow the others time to retreat. Wounded eleven times, De Sabran almost sank with his ship, literally wrecked by the fire of eight British ships. De La Clue escaped the ambush and aimed for the coast of neutral Portugal. But near Lagos the French commodore was attacked just the same by Boscawen, who ignored the neutrality of the Lusitanian kingdom, capturing and partly destroying the French squadron. The five ships that had taken the wrong route and reached Cadiz were blocked there. When Choiseul heard of the defeat at Lagos he decided to gather together sufficient forces to at least attempt an invasion of Scotland; the task was entrusted to Marshal Conflans, who despite his title was a naval officer. Choiseul’s plan consisted of 5 battleships escorting the transport ships (each carrying 150-200 soldiers) accompanied by other smaller vessels. Conflans insisted on the involvement of the whole Brest squadron in this operation, although it was greatly inferior to the English Channel squadron commanded by Admiral Hawke. Choiseul decided that the transport squadron heading for the Scottish Clyde coast should be preceded by the battle squadron, to avoid total destruction of the slow transport ships in the event of conflict with the enemy. Conflans was forced to follow the Minister’s orders and at the beginning of November 1759 he gathered together the Brest’s battle squadron, reinforcing it with the few ships under the command of Admiral Bompart, who had recently returned from the West Indies. Bompart managed to reach Brest on 6th November thanks to a storm which forced the English squadron watching the terminal to take refuge in the port of Torbay. On the 14th, Conflans left Brest and set sail with his warships towards Great Britain, immediately pursued by Hawke’s 23 ships, which had left Torbay in the meantime. After a series of events, Conflan’s squadron turned towards Quiberon Bay, which was considered dangerous because it was shallow. Conflans wrongly thought that Hawke would not risk running his ships aground; these had now been joined by another 4 ships with 50 cannons each, under the command of Admiral Duff. Instead of giving up, Hawke closed in on the French and despite the dangerous sandy seabed, attacked Conflans’ 17 vessels inside the bay. It was 20th November. The English prevailed and the French squadron was defeated and dispersed. The flagship Soleil Royale and the 14 ruined, surviving ships, some of which would sink later, were obliged to seek refuge in watercourses. The English only lost two ships. Conflans’ defeat shattered Choiseul’s dream. England was safe, and stronger than ever. After the battle of Quiberon, the British fleet never again faced substantial French squadrons. Free to act against the undefended French colonies, they completed the isolation of the enemy’s entire overseas empire.

1759 was a decisive year in the Seven Years’ War. Over 12 months the British navy obtained important victories: they beat France in Quiberon, conquered Quebec, occupied the island of Guadeloupe in the West Indies and the colony of Goree on the west coast of Africa. Admiral’s Pocock victories over Commodore d’Aché in the Indian Ocean marked the end of French trade and military activity in India. The loss of Canada and India were caused by France’s evident inability to project its military power at a distance. Deprived of its sources of raw materials, France fell into an unprecedented economic crisis. “In 1760,” writes Troude in Batailles Navales de la France, “the country’s resources were exhausted”. “Already in 1758″, adds Lapeyrouse in Histoire de la Marine, “the fall in trade due to English battle cruisers, the lack of good ships and the scarcity of reinforcements forced the French government to turn to extreme measures like piracy”.

However, the French “pirates”, despite their brilliant attacks on British traffic, could not alter a irreparably compromised situation. Even though in 1759 the French pirates managed to destroy or capture 240 vessels, almost all of small tonnage, the English dockyards made good the losses very quickly. While French trade was diminishing quickly due to enemy cruisers, British merchant traffic continued to increase thanks to the powerful transport fleet which in 1761 numbered 8,000 ships.

Even Spain’s late entry in the war as France’s ally (decided by the diplomatic agreement known as the Family Pact, agreed by the two monarchs on 15th August 1761) could not be of service to Versailles, and indeed simply caused the definitive breakdown of Spain’s power. That nation’s futile intervention was not only due to political advantage. For years Madrid had protested in vain against the attacks by “pirates” and by British regular ships, against their cargo ships. “During the Seven Years’ War”, writes the English historian Mahon in his History of England, “the Spanish flag was not always respected by British battle cruisers.” “In 1758,” adds Campbell in Lives of the Admirals, “no less than 176 neutral ships loaded with products from the French colonies fell into English hands.” Alfred T. Mahan actually admits that “the fact that the English had unlimited naval power led them to show very little respect for the basic rights of neutral nations”. The latter rightly wished to maintain trade relations with all the belligerent nations, France included. Spain therefore had good reason to take the stance which, as we know, would accelerate its political and military deterioration at a European and global level. England definitely looked favourably on the participation of an adversary lacking in military preparation but well-supplied with rich colonies to be plundered. Spain’s imprudent declaration of war against Britain made it easy for the latter to extend her expanding horizons even further. Thus London was able to engulf the Spanish colonies as well as the French ones at the end of a rapid and victorious series of naval operations. In 1761 the English fleet had reached 120 warships (plus the reserve ships and high number of minor naval vessels) armed with 70,000 trained officers and crew, mostly war veterans. The French navy, on the other hand, still had 77 warships in 1758, while the following year it had no more than 42 (27 had been captured and 8 destroyed by the enemy during the battles of ‘59). When Madrid declared war on England, the Spanish navy (on which the French seemed to rely so heavily) could only count 50 armed ships with barely-trained crew. At the end of the North American campaign, Spain’s entry into the war was a disadvantage for the French-Canadian forces. Not only did Madrid take care not to open a second front on the American continent, as Montcalm had hoped (he was counting on Spanish offensive against South Carolina, to relocate Anglo-American troops from the shaky Canadian front), but Spain did not even manage to engage its Atlantic fleet in battle against the British convoys. On the contrary, the fighting fleet and the English “pirates” fairly easily conquered the most important Spanish strongholds of the New World, taking huge spoils and reinforcing their presence in the Atlantic and elsewhere. After the formal declaration of war (1st May 1762) Spain did not attempt any offensive worthy of note against the British; indeed, Spain was immediately forced into a defensive position. At the end of May ‘62, Admiral Pocock’s squadron (which had returned in March from operations in the Indian Ocean) set sail for the important Spanish stronghold of Havana in Cuba, and conquered it after a 40-day siege. During the fighting, the English captured or sank 12 enemy ships anchored in the port. A few months later a second British squadron set sail for Manila, in the Philippines, and conquered it in October along with the whole archipelago. The occupation of the tactical naval base in Manila and the simultaneous capture by the English of two large Spanish galleons (from Acapulco and Lima) – transporting silver treasure from Latin America to Cadiz with a value equivalent to 7 million US dollars today – were decisive factors in the fall of Spain and its consequent surrender. After the loss of its most important “pirate” naval base in Fort Royal, Martinique (conquered on 12th February 1762 by Admiral Rodney) and the islands of Grenada, Santa Lucia and Saint Vincent, France was no longer a source of anxiety for the British Admiralty. The disappearance of France’s war fleet from the oceans caused the collapse of Versailles’ economic policy. “French international trade,” notes Campbell in Lives of the Admirals, “was almost completely destroyed, while the British merchant fleet grew in number and strength. The English war expenses were generously covered thanks to the income from a flourishing and safe international trade network. In that period (1760-1) English merchants made use of 8000 vessels”.

Having routed France and her Spanish allies from the seas England turned her attention to Portugal, her traditional ally. The Lusitanian monarch had been futilely threatened by the inept French and Spanish sovereigns and asked Great Britain for help; Britain sent a fleet with an army on board to Portugal. As usual the British were victorious over the scanty French-Spanish naval forces. Thanks to this intervention Great Britain obtained from Portugal free access to all its metropolitan and colonial naval bases and thus further improved the logistic and support apparatus available to the Royal Navy.

The Paris Peace Treaty of 1763 which decreed the end of the Seven Years’ War made England the greatest and most feared naval power – and consequently, the richest nation – in the world.

As one contemporary French historian remarked, “At the end of this war England found herself holding the whole of the North American and Indian continents. These two huge markets served to develop her trade and industry on an international scale”.

[1] Clowes, W., The Royal Navy: A History from the Earliest Times to 1900.:

In 1758 Admiral Boscawen was ordered to attack and capture the stronghold of Louisburg. In February Boscawen set sail from Portsmouth for Halifax, the logistic base for the whole operation. After passing the winter the English fleet took on board General Jeffery Amherst’s army (Admirals Rodney Brydges, Edward Hughes and Major General James Wolfe were also part of the expedition) and on 28th May sailed for Gabarus Bay (Louisburg) . The fleet consisted of 167 ships of all types but was scattered by a storm and most of the fleet was unable to rejoin the rest until 2nd June […]. The attack on the fortress began on 13th June. Protected by the cannons of the warships Kennington, Halifax, Diana, Gramont, Shannon, Sutherland and Squirrel, three combat groups of Amherst’s army on board launches landed with not inconsiderable difficulty due to French reprisals and the strong undertow. The main group under Wolfe’s orders managed to create a strong bridgehead on the beach where the English lay in ambush, repelling French attacks with swords. Due to the adverse sea conditions the English contingent which had landed was unable to communicate with the ships […] On 9th July the French attempted a last, violent attack supported by the artillery from the ships in port but were repelled. On 21st July, when the whole of Amherst’s contingent had landed, the English vessels opened cannon fire on the anchored French ships setting fire to Entreprenant (one of the largest ships), Célèbre and Capricieux (the French squad of Louisburg commanded by M. De Beaussier, numbered 6 warships and a few frigates). At that point Beaussier decided to block the access to the port by sinking there Apollon, Fidèle, Biche and Chèvre. On 26th July, when the situation worsened, the command of the French garrison decided to surrender. […] In the following days General Amherst’s troops occupied the stronghold and the whole island of Cape Bretone. Admiral Boscawen sent a ship to England with news of the victory and the enemy’s captured flags. Given the importance of the event these were displayed in St. Paul’s Cathedral in London.

[2] Clowes, W., The Royal Navy: A History from the Earliest Times to 1900.:

In spring 1759 the English Supreme Command mounted a large-scale multiple offensive against Canada. For this plan General Jeffery Amherst gave part of his army the task of conquering Fort Niagara and the French-Canadian outposts of Lake Erie. Brigadier-General Prideaux was to attack the former target while the second would be attacked by Brigadier-General Stanwik’s troops. Given the features of the land (rich in rivers and lakes) several Naval units were added to these two English columns with the task of building rafts and boats to transport men and vehicles. On 20th May Prideaux left Schenectady and followed the river Mohawk upstream to Oswego and on to Fort Niagara. During this manoeuvre Prideaux was killed and command of the unit was passed to Sir William Johnson, colonel of the colonial troops, who attacked and conquered the French fort on 25h July. On his return to Oswego to stock up with provisions and weaponry Johnson ordered Brigadier-General Gage and Captain Joshua Loring to build a new bastion and two large vessels to cross Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence river. In the meantime Stanwik’s column stripped the French of all their posts along the banks of Lake Erie, and a fleet of vessels immediately sailed there, which had been promptly built by the detachment of shipwrights. General Amherst’s large expedition to the important stronghold of Ticonderoga was also supported by numerous carpenters and shipwrights from the shipyards of the Atlantic coast. These men supplied Amherst with the necessary means (rafts and launches) to sail north up Lake Champlain.

Author’s Note:

The Naval squad that transported Major-General James Wolfe’s army to Quebec in spring of 1759 was led by vice-admiral Charles Saunders and rear-admirals Charles Holmes and Philip Durell. It consisted of two vessels with 50 cannons each, 20 warships (with more than 30 cannon each), several frigates and smaller boats suitable for river navigation. Before the operation against Quebec some of this fleet under the command of Durell was already anchored in the port of Halifax. On 23rd May 1759, in accordance with orders received from London, Durell left Halifax and transferred his squad to the island of Bic on the St. Lawrence estuary, where they dropped anchor and awaited the rest of the fleet. Holmes had left England at the end of winter and reached him at the end of May, while Saunders and Wolfe’s squad left Spithead on 17th February and headed for Louisburg where part of the local garrison came on board. Saunders left Louisburg on 1st June and on the 23rd finally joined Durell’s ships near the island of Coudres. Here the English took on board expert French navigators who apparently volunteered to steer the English ships down the St. Lawrence. Saunders left Durell’s ships at Coudres as a rearguard and sailed back up the large river to Quebec, the capital of New France. On 26th June after a hard voyage on board the Stirling Castle (captained by Michael Everitt) he moored near the Isle d’Orleans a few miles from Quebec. Great caution was necessary in landing as General Montcalm, commander-in-chief of the French-Canadian garrison, had had all buoys and floating signals useful in navigating this difficult watercourse removed from the expanse of water in front of the fort. Montcalm had also armed two old sailing ships to guard the St. Charles river separating the city from the entrenched posts of Beauport, where most of his army was lined up.

Lascia un commento

Devi essere connesso per inviare un commento.