The purpose of this article is to give a detailed report of what the Italian military aviation did to help the connection and interchanges of information between the allied but so distant countries such as Italy, Germany and Japan, during the Second World War. A research about the exploit of some Italian pilots who, overcoming lots of difficulties, flew from Rome to Tokyo in 1942.

During World War II the Italian aero-naval forces carried out several special missions, which – due to many technical and political implications – became real exploits. These raids – most of which successful – are almost unknown: partly because the top secret documentation got lost or destroyed after the armistice between Italy and the Allied Forces on September 8th 1943 and partly due to the Italian mental attitude to forget quickly wars and all the suffering related to them.

After the attack on Pearl Harbour on December 7th 1941, Japan was paradoxically but immediately cut off from his European Axis allies and after the interruption of the regular aero-naval links between Italy, Germany and Japan (on September 26th 1940 these three nations had subscribed an agreement of mutual military and economical assistance, known as Tripartite Pact) the military high commands of Rome and Berlin began to plan secret operations to reach the Far East by air means.

The need of supplying and exchanging rare raw materials (a need which was, however, equally felt by the Japanese) and that of co-ordinating – through the exchange of military advisers, plans and secret codes – the operations against the allied forces, fairly increased both the imagination and the project skill of the Axis engineers. Amongst the many programmes drawn up and carried out to connect Europe to Japan, the Rome-Tokyo raid has a relevant role. Given the huge distance between the two countries, in January 1942, general Rino Corso Fougier (commander in chief of the Italian air forces) applied for a consultation to a group of professional pilots who 1940 had organised several special flights connecting Italy to South America and many supply missions in 1940-41 to the isolated Italian strongholds in East Africa (Gimma and Gondar). These few courageous men had employed particular transport aircraft such as the Savoia-Marchetti SM83, the SM75 and the SM82.

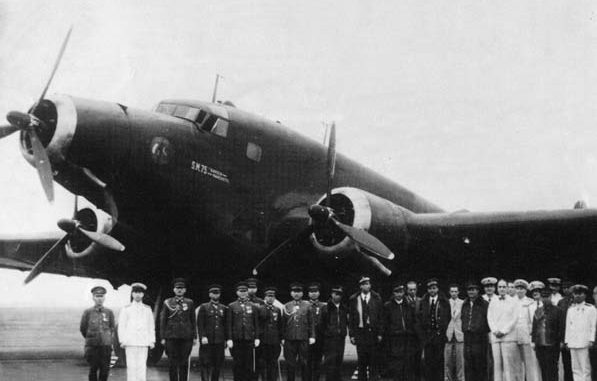

In order to complete successfully the incredible non-stop mission, the specialists chose a Savoia-Marchetti SM75 which had a better fuel range than the SM82, notwithstanding the wider cargo capacity of the latter.

The SM75 was a solid monoplane designed before the war for civilian and military transport purpose on the long distance. This plane was equipped with three 750 HP Alfa Romeo 128 RC18 engines. It weighted 9,500 kilograms without loading and over 22,000 kilograms full loaded1. The craft to be utilised for this particular mission had to be modified in some characteristics. Manned with 4/5 members, the plane had a 200 kilos cargo capacity and supplementary tanks for 8,000 kilometres of range at a cruise speed of about 300 km/h at 3,500/5,000 meters of altitude.

Initially the command chose for the mission the following men: lieutenant colonel Amedeo Paradisi (who had performed the Grand Prix 1937 Istres-Damascus-Paris and the 1938 Raid Rome-Dakar-Rio de Janeiro); captain Publio Magini (a skilled pilot pioneer in nightflights); wireless operator Ezio Vaschetto and flight engineer Vittorio Trovi. On May 9th 1942 this crew made a 28 hours trial flight on board of an SM75, reaching Asmara (former Italian colony of Eritrea, at that time already occupied by the English armies) to launch propaganda leaflets on the town (“Italian colonists, Rome is not forgetting you. We shall come back!”).

On May 11th 1942, returning from Eritrea, the SM75 GA (Grande Autonomia stands for long range) was checked up by several trials carried out by the Savoia-Marchetti mechanics. Unfortunately the plane – during a very short flight from Rome Ciampino to Guidonia airport (50 km distance) – was obliged to try an emergency landing because the three engines simultaneously broke down. In the accident the plane crashed and went totally lost. Commander Paradisi lost his right leg but the other members of the crew were safe. After the shock, the whole staff of mechanics, technicians and pilots managed to rebuild another craft in an incredible short time, so that on June 9th 1942 the brand new ‘copy’ was ready. The new crew was integrated by captain Mario Curto, second lieutenant Ernesto Mazzotti (an aerologist specialised in broadcasting), while the co-ordination of the whole operation was in charge of lieutenant colonel Antonio Moscatelli.

Finally, on June 29th 1942 at 05.30 am the SM75 GA RT (for Rome-Tokyo) took off in command of Moscatelli from the Guidonia base to Zaporoskje (Ukrajna occupied by Germans) where it landed safely after a 2,030 kilometres flight.

On June 30th at 6.00 pm – after the last checks and after loading some cases filled up with top secret documents and ciphers to be delivered to the Italian embassy in Tokyo – the Italian craft took off from an only 700 meters long airfield, overloaded with tanks containing 10,300 litres of fuel. Onboard, there were: a five members crew with their own arms and equipment, about 5 kilograms of food and medicals and about 10 litres of fresh water. Nothing more than this. The orders were that in case of emergency landing in Russian territory they had to burn the plane together with the precious top secret cargo. As the Japanese did not intend to jeopardise their relations with the Russian government at that time, there was no official document addressed to Japanese personalities onboard the craft2. Notwithstanding the complete absence of radio transmission, while it was flying over Stalino and Volga’s delta, the SM75 was spotted by the Russian antiaircraft heavy artillery and was even intercepted by a fighter (probably a Yak) that fortunately was unable to shoot it down.

In his late memories, commander Moscatelli writes about this event: “We felt the clear sensation that our route was known to the Russians”. The SM75 however carried on its long journey flying over Lake Aral’s north coast, cutting off Lake Baikal and the Tarbagatai Mountains to reach the Gobi Desert’s skies. The board maps happened to be inaccurate, particularly concerning the orographical characteristics of the territory, so that the aeroplane was compelled to fly at a higher altitude – up to 5,000 meters – in order not to be discovered, causing the crew a difficult respiration and running off the supply of oxygen faster than scheduled.

During the second part of the raid, the weather got worse because that eastern zone is influenced by winds and rains typical of the monsoon summer, causing a very difficult astronomic navigation to the crew. In addition, flying over Mongolia, the SM75 was shaken by a violent sand tempest that reached it at 3,000 meters of altitude. However commander Moscatelli succeeded in maintaining the route and on June 30th at 10.00 pm he located the Yellow River. On July 1st at 3.30 pm the three-engined SM75, almost running off fuel, landed on a 1,300 meters strip at Pao Tow Chen airfield, situated in inner Mongolia occupied by the Japanese. The Italian crew was welcomed by the Japanese Air Force of Hansi District general in charge, together with a military delegation and by two Italian military attachés expressly arrived from Tokyo (captain Roberto De Leonardis and captain Enrico Rossi).

The day after, the Italian craft reached Tokyo with a 2,700 km flight, after changing its flags and signs with the Japanese ones, in order to avoid being shot down by mistake and having on board a Japanese captain as an interpreter. On July 1st at 8.00 pm the plane landed definitively at Tokyo airport, welcomed enthusiastically by the many Italian delegates. The Japanese, on the other hand, just seemed to be friendly, but nothing more. Maybe this behaviour was mainly due to the fear of annoying the Soviet Union, but perhaps the fact of having not succeeded in projecting an aircraft with the same characteristics of the SM75 caused them some kind of regret.

The German military attaché in Tokyo was attending the event at the airport and the celebrations at the Italian embassy soon after. By transmitting in code he informed about the successful Italian raid the fieldmarshall Herman Goering, who promptly answered back with his warmest congratulations to general Fougier. It seems that Goering’s staff had a very hard time that day: the German fieldmarshall felt like shouting at all of them, accusing his technicians for not even being able to emulate and challenge “those damned maccaroni comrades”. Actually, the SM75 GA RT raid represented something really exceptional, given the times and the circumstances.

On July 16th – after a two weeks’ rest and celebration – the Italian crew reached again Pao Tow Cheng without problems. Here, after changing the Japanese signs, checked up the craft and fuelled 21,000 litres, the plane took off again on July 18th at 9.45 pm, going straight westbound. The journey back followed the same route, but was troubled by rains, clouds, frequent variations of temperature, and very dangerous ice weights on the wings. Once reached the Caspian Sea, captain Moscatelli tried to get in contact with the Italian base of Stalino, but unfortunately without success. The Soviets did not intercept the plane and on July 20th at 2.10 am the SM75 landed at the Odessa airfield after a 6,350 kilometres mission lasted 29 hours and 25 minutes. A few days after in Guidonia captain Moscatelli and his crew were decorated by Mussolini himself. This was the first and last Italian long distance raid to the Far East, because general Fougier – due to the high costs and many political and logistics reasons – decided to stop such missions definitively. However the important knowledge and experience obtained from this experiment allowed the Germans to establish in 1944 a series of similar air links with Japan, carried out by the big four-engined transport aircraft Junker 290.

Notes

1 The SM75, a freight aircraft built for civilian and military purposes, was a three-engined monoplane with low embossed wings. The plane was designed by engineer Alessandro Marchetti in 1936 and the first model (no. n/c 32001) took off from the Cameri (Novara, Piedmont) trial airfield at the command of test-pilot Alessandro Passalacqua in November 1937. The aircraft was made to provide the Ala Littoria (the Italian flag company) with a modern plane able to reach middle and long distance carrying both passengers and goods. As soon as Italy declared war (June 10, 1940) the Command of the Air Force in Rome, on the experience concerning the few models already operating, decided to militarise the SM75s available in those days and increase the production of a new stock destined to long range missions after the necessary changes.

Italy’s possessions in East Africa (Ethiopia, Somalia and Eritrea) were far away, surrounded by the enemy and required urgently a plane able to fly at least 2,500 kilometres on the outward journey. And the SM75, thanks to its good performances, was fit for the purpose. The civilian version of the aircraft could easily transport 17 passengers and their baggage 1,720 kilometres away at the maximum speed of 363 kilometres per hour at an altitude of 4,000 metres. The military version, equipped with a dorsal 12.7 millimetres Breda Safat machinegun, in a Caproni-Lanciani turret, was able to carry 24 soldiers with the same performances of the basic model.

The SM75 was provided with three Alfa Romeo 126 RC.34 radial engines, each one developing 750 hp at 3,400 metres or with three Alfa Romeo 128 RC.18 engines, each one developing 860 hp at an altitude of 1,800 metres.

The prototype had a 29.68 meters wingspan, a total length of 21.60 metres and it was 5.10 metres high, while its wing surface was 118.80 square metres. The plane weighed 9,500 kilograms when totally empty and 13,000 kilograms with the maximum load.

The SM75 was able to reach the height of 4,000 metres in 17 minutes and 42 seconds and had its highest tangency at 6,250 metres. The plane was able to take off within 337 metres and to land within 280 metres. Such performances made it fit for operating even in secondary airfields.

The civilian model had a crew of four men, while the military model had a crew of five (including the machinegunner).

2 According to the previously agreed commitments with the Japanese embassy in Rome, the Italian government avoids to deliver any correspondence or even hints which might embarrass the Tokyo authorities. For security reasons, even the personal message of the Italian foreign minister Galeazzo Ciano, addressed to the Japanese war minister Hideki Tojo, is left in Italy (it will be radio-transmitted only at mission completed).

Biographic notes

Alberto Rosselli is a free-lance writer from Genoa, Italy. He has a doctorate in political sciences and is going to pursue a second doctorate in Modern and Contemporary History. He has published two essays on the English-French conflict during the Seven Years’ war in North America. He is at present working at the history of the Middle Eastern front during World War I and is going to publish the English translation of The English-French Conflict in North America. 1756-1763, whose Italian version has been listed in the Library of Congress of Washington.

Further reading on the subject

Italian language: Dimensione Cielo. Aerei Italiani nella Seconda guerra Mondiale. Roma 1975, Edizioni Bizzarri

Lascia un commento

Devi essere connesso per inviare un commento.